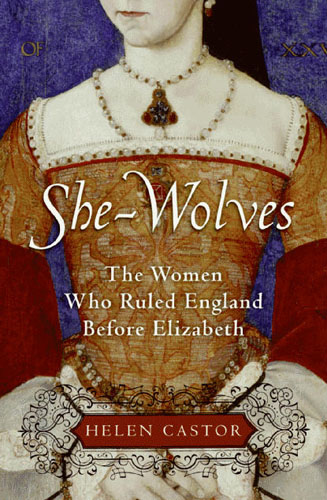

She-Wolves by Helen Castor

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

After watching The King’s Speech, I finally grew interested in the British monarchy, if just for a little while. During AP European History in high school, I was always much more interested in the Russian monarchy or defending my motherland against scurrilous claims. (What’s that? The French do what? I’m sorry, I can’t hear you over the sound of William the Conqueror taking over your island of perpetual rain and fog. Deal with it.) When I was offered the chance to review She-Wolves, I took it, curious about female power in the British monarchy, especially back when it actually was a position of political power. Unfortunately, it fell short.

She-Wolves opens in 1553 with the death of Henry VIII’s beloved son and heir, Edward VI, leading to an peculiar dilemma for the English succession—the Tudors, always a thinly male dynasty, can only offer up women to succeed Edward VI. Helen Castor uses this situation to frame four cases of female power in England; Matilda, the granddaughter of William the Conqueror, as well as Eleanor of Aquitaine, Isabella of France, and Margaret of Anjou, royal wives who used their husband’s power to forward their own case. The lives and political struggles of these women, none of whom ever ruled over England properly, add a particular depth to the rise of the first Queen of England and to the paradox of female power in a patriarchal society.

I enjoyed Castor’s juxtaposition of these four women—Matilda, Eleanor, Isabella, and Margaret—against the three women who rose to prominence after Edward’s death—Jane Grey, Mary I, and Elizabeth I. I didn’t know much about female power in England before opening She-Wolves (beyond, of course, Elizabeth I), so it was fascinating to see Matilda, the granddaughter of William the Conqueror himself, trying to assert her claim on the English throne and the duchy of Normandy after the death of her father. In medieval Europe, kings were expected to lead on the battlefield as well as politically; despite her lineage, Matilda couldn’t stand a chance against her rival, Stephen of Blois, a strapping man with plenty of military experience. Eventually, she had to change her claim to fighting for the rights of her son, Henry II, which eventually worked. Heck, just learning about how English royalty managed and eventually lost holdings in France was fascinating, combined with my readings for my History of English class. Each woman had their own trials to deal with; Eleanor of Aquitaine eventually revolted against her husband, Isabella of France had to deal with her husband’s self-destructive love and favoritism for two different men, and Margaret of Anjou’s life was consumed by the War of the Roses.

Castor opens each section with a helpful map of English holdings at the time of each woman’s birth and family trees; it’s occasionally astonishing to see how closely related the royal families of Europe were. Eleanor of Aquitaine was able to dissolve her first marriage to Louis VII, King of France, by the excuse of consanguinity—being too closely related. It was an excuse commonly used by royal men in order to cast off politically disadvantageous wives; Eleanor’s use of it was shocking. I did wish we learned more about the War of the Roses in Margaret’s section; while I could pick up bits and pieces, Castor never summarizes the conflict beyond adding another family tree of important nobles in England at the time, leaving you to pick up the pieces and try to fit them together.

In fact, this is a problem with Castor’s writing. Her research is thorough, but she’ll often gallop off without the reader, leaving the reader to double-check names and figure out who is who in this complex conflict. Her writing is clear, if a little dry and occasionally obtuse—when Castor discusses rumors that the married Eleanor is sleeping with her uncle, she declares that such a relationship would be considered adultery as well as incest. …yes, yes, it would be. For a book focused on female power, Castor focuses a great deal on the male players on the stage; obviously, I realize that politics in the Middle Ages and Elizabethan England were dominated by men, but shouldn’t a book about this women focus on them? I realize setting the stage for their lives is important, but Castor needs to learn how to summarize and condense information clearly, instead of backing up to the beginning and letting these women step out of the shadows late into their own stories. Castor begins with the birth of these women rather than the moment they became politically involved with the power struggles over the English throne. It doesn’t help that this is contrasted against starting with the Tudor succession with the void left by Edward VI, the proper place to start, making it look worse than it is. Sigh.

Bottom line: While Helen Castor’s She-Wolves is an interesting concept and certainly educational, it’s also dry and a little unaccessible. Some prior knowledge of these events, especially the War of the Roses, is required. If you’re interested, harmless; if not, there’s better.

I received this book from the publisher for review.

I’ve heard a few of the same things about this book — little dry in places and needs a map to keep all the royals in order. I still want to read it though since it is a favorite time period of mine.

Eleanor of Aquitaine has always interested me since I saw ‘The Lion in Winter’ – she must have been a fascinating woman. Though didn’t she encourage her sons to rebel against Henry rather than try to seize power herself?

The Wars of the Roses are an inherently complex period of history, even for Brits who might know more about it, and it should be a historian’s job to explain that, particularly given Margaret’s importance to the ultimate success of the Tudor dynasty.

Yes, she certainly did.

You’re absolutely right.